Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder and the most common cause of dementia worldwide. It is characterized by cognitive decline, memory loss, and behavioral changes, resulting from the accumulation of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in the brain. AD significantly impairs daily functioning and leads to a decline in quality of life for patients and their caregivers.

Epidemiology of Alzheimer’s Disease

1. Prevalence: Alzheimer’s disease accounts for 60–70% of all dementia cases. Approximately 50 million people globally are living with dementia, and this number is projected to triple by 2050 due to aging populations.

2. Onset: Most cases are late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD), occurring after the age of 65. Early-onset Alzheimer’s disease (EOAD) occurs in individuals under 65 and accounts for less than 5% of cases.

3. Sex Differences: Women are more affected than men, partly due to their longer life expectancy.

Etiology and Risk Factors of Alzheimer’s disease

Alzheimer’s disease is caused by a combination of genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors.

1. Genetic Factors:

APOE ε4 Allele: The strongest genetic risk factor for late-onset AD.

Rare Mutations: Mutations in APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2 genes lead to familial (early-onset) Alzheimer’s.

2. Neurobiological Factors:

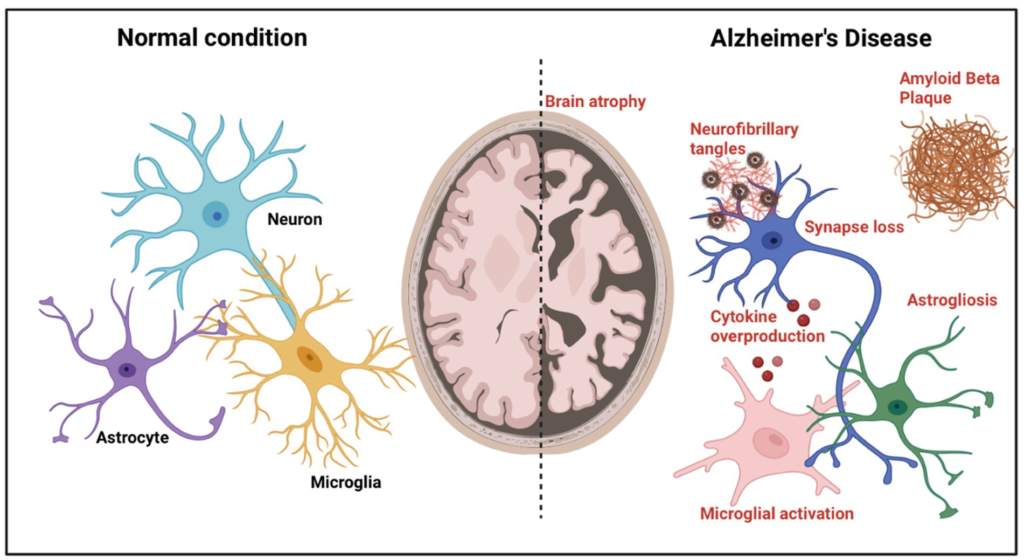

Amyloid Cascade Hypothesis: Accumulation of β-amyloid peptides forms plaques, initiating a cascade of neurotoxicity.

Tau Hypothesis: Hyperphosphorylated tau proteins form tangles, leading to neuronal death.

Neuroinflammation: Chronic activation of microglia and astrocytes contributes to neuronal damage.

3. Environmental and Lifestyle Risk Factors:

Age: The strongest risk factor; incidence doubles every 5 years after age 65.

Cardiovascular Health: Hypertension, diabetes, and obesity increase risk.

Lifestyle: Smoking, physical inactivity, and poor diet are associated with increased risk.

Education: Lower levels of education and reduced cognitive engagement increase vulnerability.

4. Other Risk Factors:

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI): Linked to increased risk of dementia.

Depression: Long-term depression may increase susceptibility.

Pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s disease

1. Amyloid Plaques: β-amyloid is derived from the cleavage of amyloid precursor protein (APP). Misfolded β-amyloid aggregates into plaques, disrupting synaptic function and triggering neuroinflammation.

2. Neurofibrillary Tangles: Composed of hyperphosphorylated tau protein, tangles disrupt microtubule stability, leading to impaired intracellular transport and neuronal death.

3. Synaptic Dysfunction: Progressive loss of synapses and reduced neurotransmitter levels, particularly acetylcholine, contribute to cognitive decline.

4. Neuroinflammation and Oxidative Stress: Chronic inflammation and reactive oxygen species exacerbate neuronal damage.

5. Brain Atrophy: Significant shrinkage occurs in the hippocampus, amygdala, and cortical regions responsible for memory and cognitive processing.

Clinical Features of Alzheimer’s disease

1. Cognitive Symptoms:

Memory Loss: Difficulty recalling recent events, progressing to long-term memory impairment.

Language Deficits: Word-finding difficulty, reduced vocabulary, and difficulty following conversations.

Executive Dysfunction: Impaired problem-solving, planning, and decision-making.

Visuospatial Problems: Difficulty recognizing faces, objects, and navigating environments.

2. Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms: Depression, anxiety, and apathy are common.

Agitation, aggression, and paranoia may occur in advanced stages.

3. Functional Impairments: Difficulty performing daily activities like dressing, cooking, and managing finances.

4. Neurological Symptoms: In later stages, motor deficits, seizures, and dysphagia may develop.

Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease

1. Clinical Assessment: Detailed history of cognitive, functional, and behavioral changes. Cognitive testing using tools such as the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) or Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA).

2. Biomarkers:

CSF Analysis: Decreased β-amyloid levels and increased tau levels in cerebrospinal fluid.

Neuroimaging:

MRI: Shows brain atrophy, particularly in the hippocampus and medial temporal lobes.

PET Scans: Detect amyloid deposition using tracers like florbetapir or measure glucose metabolism using FDG-PET.

3. Differential Diagnosis: Rule out other causes of dementia, such as vascular dementia, Lewy body dementia, and frontotemporal dementia.

Treatment of Alzheimer’s disease

There is no cure for Alzheimer’s disease, but treatments focus on slowing disease progression and managing symptoms.

1. Pharmacological Therapy:

Cholinesterase Inhibitors: Improve cognitive symptoms by increasing acetylcholine levels.

Examples: Donepezil, Rivastigmine, Galantamine.

NMDA Receptor Antagonist: Protects neurons from excitotoxicity caused by excess glutamate.

Example: Memantine.

Antipsychotics and Antidepressants: Used for managing agitation, aggression, and depression.

2. Non-Pharmacological Interventions:

Cognitive Stimulation Therapy: Engages patients in mentally stimulating activities.

Behavioral Therapy: Addresses challenging behaviors through environmental modifications.

Lifestyle Interventions: Physical exercise, a Mediterranean diet, and social engagement may reduce progression.

3. Emerging Therapies:

Monoclonal Antibodies: Target amyloid plaques (e.g., aducanumab).

Gene Therapy: Investigational therapies targeting genetic mutations.

Neuroprotective Agents: Focus on reducing oxidative stress and neuroinflammation.

Conclusion

Alzheimer’s disease remains a major public health challenge with significant personal and societal impact. Ongoing research into its pathophysiology and treatments offers hope for better management and eventual prevention.