Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) refers to liver damage caused by excessive alcohol consumption. The liver processes alcohol, but when intake exceeds the liver’s capacity to metabolize it, toxic byproducts accumulate, leading to liver injury. ALD encompasses a range of liver conditions, from fatty liver to cirrhosis, and is one of the most common causes of liver disease worldwide.

Stages of Alcoholic Liver Disease

1. Fatty Liver (Alcoholic Steatosis):

Pathophysiology: The liver cells accumulate fat due to the toxic effects of alcohol and its metabolites. Alcohol interferes with lipid metabolism, leading to lipid deposition in hepatocytes.

Symptoms: Often asymptomatic, but can include fatigue, abdominal discomfort, and mild hepatomegaly (enlarged liver).

Diagnosis: Liver function tests (LFTs) showing elevated liver enzymes, ultrasound showing fatty infiltration, and exclusion of other causes.

Reversibility: Reversible with abstinence from alcohol.

2. Alcoholic Hepatitis:

Pathophysiology: Chronic alcohol consumption leads to inflammation of the liver (hepatitis), which can cause damage to liver cells. This results in the release of inflammatory cytokines and recruitment of immune cells, further harming the liver.

Symptoms: Jaundice, fever, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, and hepatomegaly. In severe cases, patients may develop ascites (fluid accumulation in the abdomen) and hepatic encephalopathy (confusion due to liver dysfunction).

Diagnosis: Blood tests showing elevated bilirubin and liver enzymes (AST, ALT), liver biopsy, or imaging techniques.

Management: Abstinence from alcohol is the cornerstone of treatment. Corticosteroids may be used in severe cases to reduce inflammation, and nutritional support is essential.

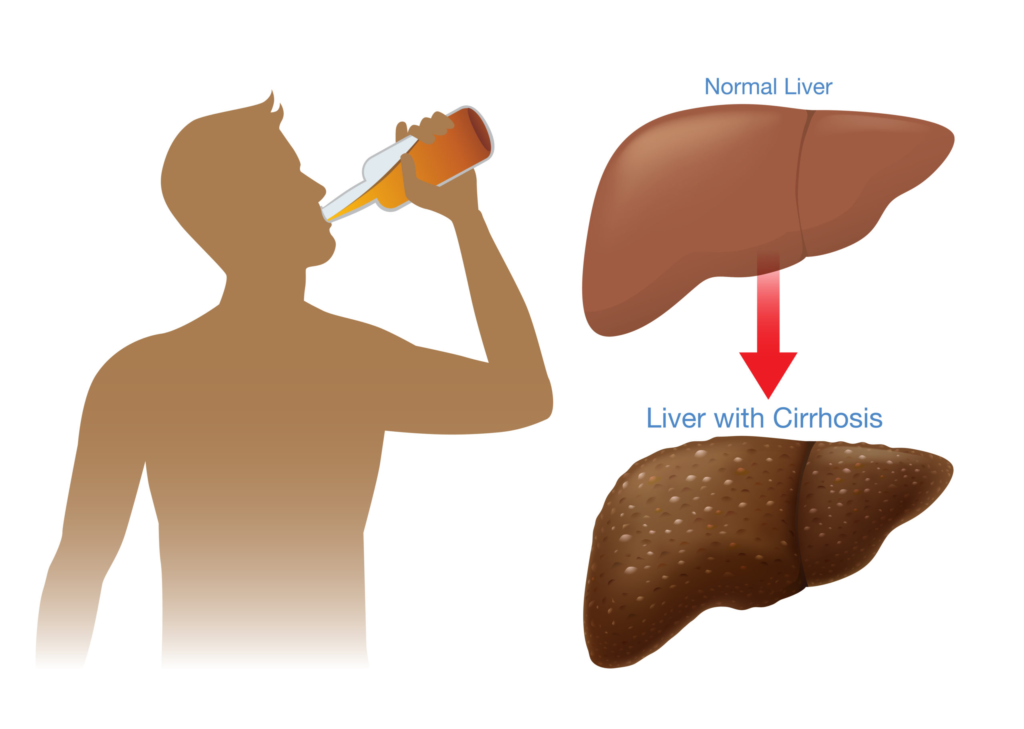

3. Alcoholic Cirrhosis:

Pathophysiology: Chronic alcoholic hepatitis leads to scarring (fibrosis) and eventually cirrhosis. In cirrhosis, the liver’s architecture is distorted, and liver function deteriorates. The damage is irreversible at this stage.

Symptoms: Severe fatigue, weight loss, jaundice, ascites, gastrointestinal bleeding (due to esophageal varices), and hepatic encephalopathy.

Diagnosis: Liver function tests showing high bilirubin, low albumin, elevated liver enzymes, imaging (ultrasound, CT scan, MRI), and liver biopsy confirming cirrhosis.

Management: No cure for cirrhosis, but the progression can be slowed with abstinence. Patients may require medications for complications (e.g., diuretics for ascites, beta-blockers for varices) and liver transplantation in advanced stages.

4. Hepatic Encephalopathy:

Pathophysiology: As liver function declines, the liver’s ability to detoxify ammonia and other toxins diminishes. These toxins accumulate in the bloodstream and affect the brain, causing confusion, lethargy, and eventually coma.

Symptoms: Altered mental state, confusion, personality changes, drowsiness, and in severe cases, coma.

Diagnosis: Blood ammonia levels, clinical assessment, and exclusion of other causes of encephalopathy.

Management: Lactulose (to reduce ammonia levels), rifaximin (antibiotic), and treatment of underlying liver disease.

Risk Factors for Alcoholic Liver Disease

Chronic Heavy Drinking: The primary risk factor. The amount of alcohol consumed, the duration of consumption, and the pattern of drinking all contribute to the development of ALD. Generally, women are more susceptible to liver damage at lower levels of alcohol intake than men.

Genetic Factors: Genetic predisposition plays a significant role in susceptibility. Variants of genes encoding alcohol-metabolizing enzymes (e.g., ALDH2) and the immune response (e.g., TNF-α) have been implicated in the development of ALD.

Nutritional Deficiencies: Chronic alcohol consumption often leads to malnutrition, particularly deficiencies in vitamin B1 (thiamine), folate, and other essential nutrients, which can exacerbate liver damage.

Co-existing Liver Conditions: Pre-existing liver conditions (e.g., viral hepatitis) can accelerate the progression of ALD.

Pathophysiology of Alcoholic Liver Disease

1. Alcohol Metabolism:

Ethanol is primarily metabolized in the liver by enzymes:

Alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH): Converts ethanol to acetaldehyde, a toxic substance.

Aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH): Converts acetaldehyde to acetate, which is then broken down to carbon dioxide and water.

Cytochrome P450 2E1 (CYP2E1): Plays a role in metabolizing ethanol, producing reactive oxygen species (ROS) that damage liver cells.

2. Toxic Effects of Alcohol:

Acetaldehyde: Toxic byproduct that forms during alcohol metabolism. It damages hepatocytes, promotes inflammation, and alters liver cell function.

Oxidative Stress: ROS generated by CYP2E1 cause cellular damage and inflammation in the liver, contributing to fibrosis.

Inflammation: Alcohol triggers immune system activation, which results in inflammatory cytokine release and further liver injury.

Fibrosis and Cirrhosis: Chronic inflammation leads to the activation of hepatic stellate cells, which produce collagen and cause fibrosis. Over time, this progresses to cirrhosis.

Clinical Features of Alcoholic Liver Disease

1. Fatty Liver: Generally asymptomatic, may present with mild right upper abdominal discomfort or fatigue. Liver enlargement may be detected on physical examination.

2. Alcoholic Hepatitis: Fever, jaundice, right upper quadrant pain, and hepatomegaly. Severe cases may present with ascites, gastrointestinal bleeding, and altered mental status (hepatic encephalopathy).

3. Alcoholic Cirrhosis: Fatigue, weight loss, ascites, jaundice, and easy bruising. Portal hypertension complications: variceal bleeding, splenomegaly, and encephalopathy.

Diagnosis of Alcoholic Liver Disease

1. Blood Tests: In patients with alcoholic hepatitis, elevated liver enzymes are often observed, with aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels typically surpassing alanine aminotransferase (ALT). This pattern is particularly indicative of alcoholic liver injury. In cirrhosis, laboratory findings often reveal increased bilirubin levels, reflecting impaired liver function, along with reduced albumin, which is a marker of liver’s synthetic capacity. Additionally, prolonged prothrombin time can be noted, signifying coagulopathy, a common complication of cirrhosis. A complete blood count (CBC) may show anemia or thrombocytopenia, both of which are associated with liver dysfunction, either due to hypersplenism or impaired bone marrow function. These changes in laboratory values are crucial for diagnosing and monitoring liver diseases.

2. Imaging: Ultrasound is a primary imaging modality in liver disease, often revealing hepatic steatosis (fatty liver), structural changes associated with cirrhosis, and signs of portal hypertension such as splenomegaly or collateral vessel formation. In advanced stages of liver disease, computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be employed to provide a more detailed assessment of liver structure, detect complications like hepatocellular carcinoma, or evaluate the extent of portal hypertension. These imaging techniques are invaluable in diagnosing, staging, and managing liver conditions.

3. Liver Biopsy: A liver biopsy serves as a definitive diagnostic tool, particularly useful in distinguishing alcoholic steatosis from other liver conditions. This procedure allows for microscopic examination of liver tissue, enabling accurate grading of the severity of liver damage, including the extent of fibrosis and the presence of cirrhosis. By providing detailed insights into the underlying pathology, a liver biopsy is crucial for tailoring treatment strategies and predicting disease prognosis.

Management of Alcoholic Liver Disease

1. Abstinence from Alcohol: The most important factor in managing ALD. Alcohol cessation halts or slows disease progression and improves survival.

2. Nutritional Support: Malnutrition is common in ALD patients. Nutritional therapy, including vitamin supplementation (thiamine, folate), is essential.

3. Medications:

Corticosteroids: Used in severe alcoholic hepatitis to reduce inflammation.

Pentoxifylline: An alternative to corticosteroids in some cases of alcoholic hepatitis.

Liver Transplantation: Considered in cases of advanced cirrhosis or acute-on-chronic liver failure.

4. Management of Complications:

Ascites: Treated with diuretics (spironolactone, furosemide) and paracentesis.

Portal Hypertension: Managed with beta-blockers or endoscopic variceal ligation.

Hepatic Encephalopathy: Treated with lactulose and rifaximin to reduce ammonia levels.

Prognosis of Alcoholic Liver Disease

Fatty Liver: Reversible with abstinence from alcohol. With continued drinking, it may progress to alcoholic hepatitis.

Alcoholic Hepatitis: Can be reversible with abstinence and treatment, but severe cases may lead to cirrhosis or liver failure.

Alcoholic Cirrhosis: Irreversible liver damage, and patients may require liver transplantation. Without transplantation, the prognosis is poor, with a high risk of liver cancer and death.

Prevention of Alcoholic Liver Disease

1. Limiting Alcohol Intake: Adhering to safe drinking limits (e.g., no more than two drinks per day for men and one for women) significantly reduces the risk of ALD.

2. Public Awareness: Education on the risks of heavy drinking and the benefits of early intervention.

3. Screening: Regular screening in high-risk populations, especially those with a history of heavy drinking or other risk factors for liver disease.

Alcoholic liver disease is a preventable and potentially reversible condition if diagnosed early and managed with appropriate interventions, including alcohol cessation, nutritional support, and medical treatment. However, advanced stages like cirrhosis require careful management of complications and may eventually necessitate liver transplantation.

Visit to: Pharmacareerinsider.com