Small Intestine

Definition:

The small intestine is a vital part of the digestive system in humans and many other animals. It is a long, coiled tube that is situated between the stomach and the large intestine. Despite its name, the small intestine is actually longer than the large intestine, although it has a smaller diameter.

Anatomy:

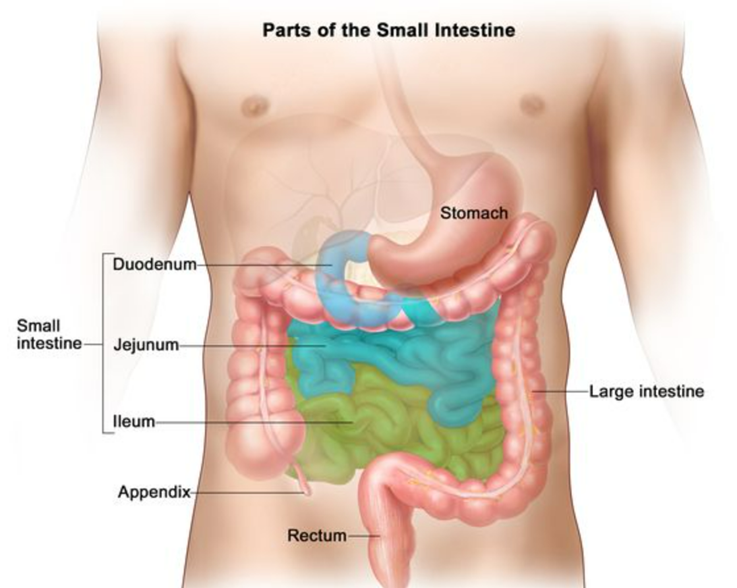

1. Sections: The small intestine is divided into three main sections:

– Duodenum: The first and shortest section, which receives partially digested food from the stomach and secretions from the pancreas and liver.

– Jejunum: The middle section, where the majority of nutrient absorption occurs.

– Ileum: The final section, which connects to the large intestine and absorbs remaining nutrients, as well as bile salts and vitamin B12.

2. Structure: The small intestine has a highly folded inner lining called the mucosa, which contains finger-like projections called villi and microvilli. These structures increase the surface area available for absorption. Additionally, numerous intestinal glands (crypts of Lieberkühn) are present in the mucosa, which secrete digestive enzymes and mucus.

3. Blood Supply and Innervation: The small intestine receives blood supply from branches of the superior mesenteric artery and is innervated by the enteric nervous system, as well as sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves.

Functions:

1. Digestion: The small intestine continues the digestion of food initiated in the stomach by breaking down carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids into smaller molecules using enzymes produced by the pancreas and intestinal mucosa.

2. Absorption: The primary function of the small intestine is to absorb nutrients, including carbohydrates, proteins, fats, vitamins, and minerals, into the bloodstream. This absorption occurs primarily in the jejunum and ileum, facilitated by the extensive surface area provided by villi and microvilli.

3. Secretion: The small intestine secretes digestive enzymes, mucus, and hormones to aid in digestion and regulate gastrointestinal motility. Additionally, bile salts, produced by the liver and stored in the gallbladder, are released into the duodenum to aid in the emulsification and absorption of fats.

4. Immune Function: The small intestine plays a role in immune defense through the presence of specialized immune cells, such as Peyer’s patches, which help protect against pathogens and regulate immune responses in the gastrointestinal tract.

Large Intestine:

Definition: The large intestine, also known as the colon, is the final portion of the digestive system in humans and other vertebrates. It follows the small intestine and is responsible for further processing the remaining food particles, absorbing water, and eliminating waste from the body.

Anatomy:

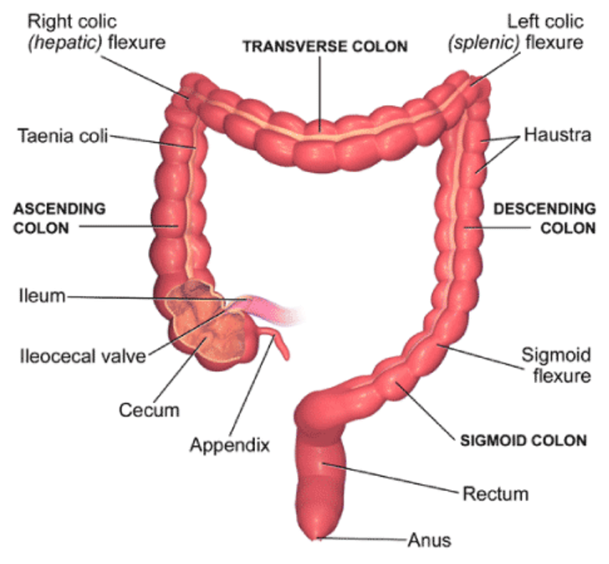

1. Sections: The large intestine consists of several segments:

– Cecum: The first part of the large intestine, which connects to the ileum of the small intestine and contains the appendix.

– Colon: Divided into four main regions: the ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon, and sigmoid colon.

– Rectum: The terminal portion of the large intestine, which stores feces before elimination.

– Anus: The opening at the end of the digestive tract through which feces are expelled from the body.

2. Structure: The large intestine has a relatively simple structure compared to the small intestine. It lacks villi and has a smooth mucosal surface with numerous intestinal glands (crypts of Lieberkühn) that secrete mucus.

3. Blood Supply and Innervation: The large intestine receives blood supply from branches of the superior and inferior mesenteric arteries and is innervated by the enteric nervous system, sympathetic, and parasympathetic nerves.

Functions:

1. Absorption of Water and Electrolytes: The primary function of the large intestine is to absorb water and electrolytes from undigested food residues, converting the liquid chyme into semisolid feces.

2. Formation and Storage of Feces: The large intestine compacts and stores fecal matter until it is ready for elimination. During this process, water is reabsorbed, and the feces become more solid.

3. Fermentation: The large intestine harbors a large population of bacteria known as the gut microbiota, which ferment undigested carbohydrates and produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and gases as byproducts. SCFAs serve as an energy source for colonocytes and play a role in maintaining gut health.

4. Defecation: When the rectum is distended with feces, sensory nerve fibers in the rectal wall send signals to the brain, triggering the urge to defecate. Defecation involves the coordinated relaxation of the internal and external anal sphincters to allow for the expulsion of feces from the body.

Comparison:

– Function: While both the small and large intestines are involved in absorption and secretion, the small intestine primarily absorbs nutrients, while the large intestine focuses on water and electrolyte absorption, as well as fecal storage and elimination.

– Structure: The small intestine has a highly folded mucosa with villi and microvilli to increase surface area for absorption, whereas the large intestine has a smooth mucosal surface with no villi.

– Digestive Enzymes: The small intestine secretes a variety of digestive enzymes to break down nutrients, while the large intestine primarily relies on fermentation by gut bacteria to digest carbohydrates.

– Length: The small intestine is much longer than the large intestine, allowing for extensive nutrient absorption, while the large intestine is shorter and primarily functions in water reabsorption and fecal formation.

In summary, the small intestine and large intestine are distinct segments of the gastrointestinal tract with specialized structures and functions. Together, they play essential roles in digestion, nutrient absorption, water reabsorption, and waste elimination, contributing to overall gastrointestinal health and homeostasis.