Drugs Used in Alzheimer’s Disease: Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a chronic, progressive neurodegenerative condition that primarily impairs memory, cognitive function, and the ability to perform daily activities. As the most common cause of dementia among older adults, Alzheimer’s accounts for approximately 60% to 80% of all dementia cases globally. First described by Alois Alzheimer in 1906, the disease is now recognized as a major public health concern, especially in aging populations.

The neuropathological features of Alzheimer’s disease include extracellular deposits of beta-amyloid (Aβ) plaques, intracellular neurofibrillary tangles composed of hyperphosphorylated tau protein, widespread synaptic dysfunction, and neuronal death. A significant neurochemical change observed in AD is the deficiency of acetylcholine (ACh), a neurotransmitter essential for learning and memory.

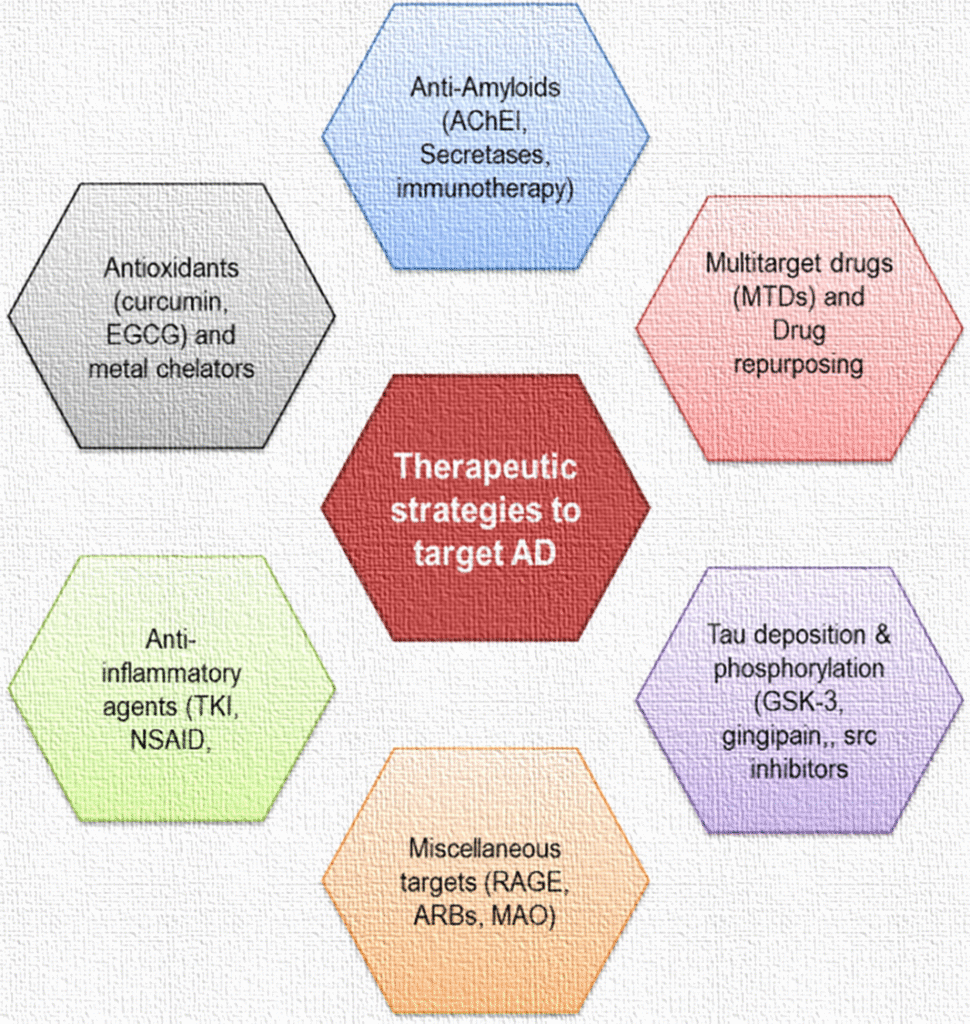

Pharmacological therapy for Alzheimer’s disease does not cure the illness but aims to manage symptoms, slow disease progression, and improve the quality of life for patients and caregivers. Current pharmacological strategies target neurotransmitter imbalances and pathological processes associated with the disease.

Drugs Used in Alzheimer’s Disease

Classification of Drugs Used in Alzheimer’s Disease

Drugs used to manage Alzheimer’s disease can be categorized based on their mechanism of action and therapeutic intent. These include symptomatic treatments that address cognitive deficits and behavioral disturbances, and disease-modifying therapies that aim to alter the underlying pathophysiology.

1. Cholinesterase Inhibitors (AChE Inhibitors)

These drugs inhibit the enzyme acetylcholinesterase, which degrades acetylcholine in the synaptic cleft. By increasing the availability of acetylcholine, cholinesterase inhibitors enhance cholinergic neurotransmission and improve cognitive symptoms in mild to moderate stages of Alzheimer’s.

- Examples: Donepezil, Rivastigmine, Galantamine

2. NMDA Receptor Antagonists

These agents modulate glutamatergic transmission by inhibiting excessive activation of N-Methyl-D-Aspartate (NMDA) receptors. Overstimulation of NMDA receptors can lead to excitotoxicity and neuronal injury. These drugs are particularly useful in moderate to severe AD.

- Example: Memantine

3. Combination Therapy

Combining cholinesterase inhibitors with NMDA receptor antagonists may offer enhanced clinical benefits in moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease by targeting multiple neurotransmitter pathways.

- Example: Donepezil + Memantine

4. Disease-Modifying Monoclonal Antibodies

These agents represent a new class of drugs targeting the accumulation of amyloid-beta plaques. They are considered disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) because they aim to slow the pathological progression of AD.

- Examples: Aducanumab, Lecanemab, Donanemab

5. Supportive and Adjunctive Therapies

These medications are used to manage neuropsychiatric symptoms such as depression, anxiety, aggression, and psychosis that frequently accompany Alzheimer’s disease.

- Antipsychotics: Risperidone, Quetiapine

- Antidepressants: Sertraline, Citalopram

- Anxiolytics: Lorazepam (used cautiously due to risk of sedation and falls)

Detailed Description of Key Drugs

1. Donepezil

- Pharmacological Class: Reversible acetylcholinesterase inhibitor

- Indications: Approved for all stages of Alzheimer’s disease

- Mechanism of Action: Inhibits acetylcholinesterase in the central nervous system, leading to increased concentrations of acetylcholine at cholinergic synapses.

- Dosage and Administration: Initiated at 5 mg orally once daily; can be increased to 10 mg/day after 4–6 weeks

- Side Effects: Nausea, diarrhea, insomnia, muscle cramps, fatigue, anorexia, bradycardia

2. Rivastigmine

- Pharmacological Class: Acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase inhibitor

- Indications: Mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease dementia

- Mechanism of Action: Dual inhibition enhances cholinergic function by preventing the hydrolysis of acetylcholine and butyrylcholine

- Dosage and Administration: Oral and transdermal forms; oral starting dose 1.5 mg twice daily; patch available in 4.6 mg/24 hr and 9.5 mg/24 hr formulations

- Side Effects: Gastrointestinal disturbances, dizziness, headache, weight loss

3. Galantamine

- Pharmacological Class: Acetylcholinesterase inhibitor and nicotinic receptor modulator

- Indications: Mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease

- Mechanism of Action: Enhances cholinergic function through dual action: inhibition of AChE and positive allosteric modulation of nicotinic receptors

- Dosage and Administration: Initial dose 4 mg twice daily; titrated gradually to 8–12 mg twice daily

- Side Effects: Nausea, vomiting, weight loss, syncope

4. Memantine

- Pharmacological Class: NMDA receptor antagonist

- Indications: Moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease

- Mechanism of Action: Blocks pathological activation of NMDA receptors, reducing calcium influx and excitotoxic neuronal damage

- Dosage and Administration: 5 mg once daily; titrated to 10 mg twice daily

- Side Effects: Dizziness, headache, confusion, constipation, hypertension

5. Aducanumab

- Pharmacological Class: Monoclonal antibody against aggregated beta-amyloid

- Indications: Mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease

- Mechanism of Action: Targets and facilitates clearance of amyloid-beta plaques from the brain

- Dosage and Administration: Intravenous infusion every four weeks

- Side Effects: Amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA), headache, hypersensitivity reactions

Mechanism of Action

Cholinesterase Inhibitors

Cholinergic neurons are significantly degenerated in Alzheimer’s disease, leading to decreased acetylcholine levels in cortical and subcortical areas. Cholinesterase inhibitors act by blocking the enzymatic breakdown of acetylcholine in the synaptic cleft, thereby enhancing cholinergic neurotransmission. This improved neurotransmission correlates with temporary improvements in cognition and behavior.

NMDA Receptor Antagonists

The NMDA receptor is a subtype of glutamate receptor involved in synaptic plasticity, memory formation, and learning. In Alzheimer’s, chronic low-level activation of NMDA receptors by glutamate can result in sustained calcium influx, leading to oxidative stress and neuronal apoptosis. Memantine selectively blocks the pathologic activation of these receptors while sparing normal physiological transmission.

Monoclonal Antibodies

These agents are designed to bind specifically to aggregated forms of amyloid-beta in the brain. Once bound, the amyloid-antibody complex is recognized and removed by the body’s immune cells. This mechanism is thought to slow or halt the progression of neurodegeneration by reducing toxic plaque buildup.

Recent Advances and Clinical Trials

Recent years have seen a surge in clinical trials exploring disease-modifying therapies targeting amyloid-beta, tau protein, and neuroinflammation. Monoclonal antibodies like Lecanemab and Donanemab have demonstrated the ability to clear amyloid plaques, with some studies suggesting potential cognitive benefits in early stages of Alzheimer’s. Ongoing trials are also exploring tau-targeting agents, neuroprotective drugs, and gene therapies.

Non-Pharmacological Approaches

While not a substitute for pharmacological treatment, lifestyle interventions like cognitive training, regular physical activity, social engagement, and a Mediterranean diet may complement drug therapy. These strategies aim to enhance neuroplasticity and cognitive reserve.

Comprehensive Table: Side Effects of Alzheimer’s Drugs

| Drug | Common Side Effects | Serious Adverse Effects |

| Donepezil | Nausea, diarrhea, insomnia | Bradycardia, QT prolongation |

| Rivastigmine | Dizziness, vomiting | GI bleeding, skin reactions (patch) |

| Galantamine | Anorexia, headache | Syncope, weight loss |

| Memantine | Confusion, dizziness | Hypertension, hallucinations |

| Aducanumab | Headache, ARIA | Edema, microhemorrhages |

Conclusion

Alzheimer’s disease presents a complex therapeutic challenge, given its multifactorial pathogenesis. Current treatment modalities primarily offer symptomatic relief with modest benefits. However, advances in disease-modifying agents, particularly monoclonal antibodies, represent a promising frontier. A multidisciplinary approach integrating pharmacological and non-pharmacological strategies is essential for optimizing patient outcomes.