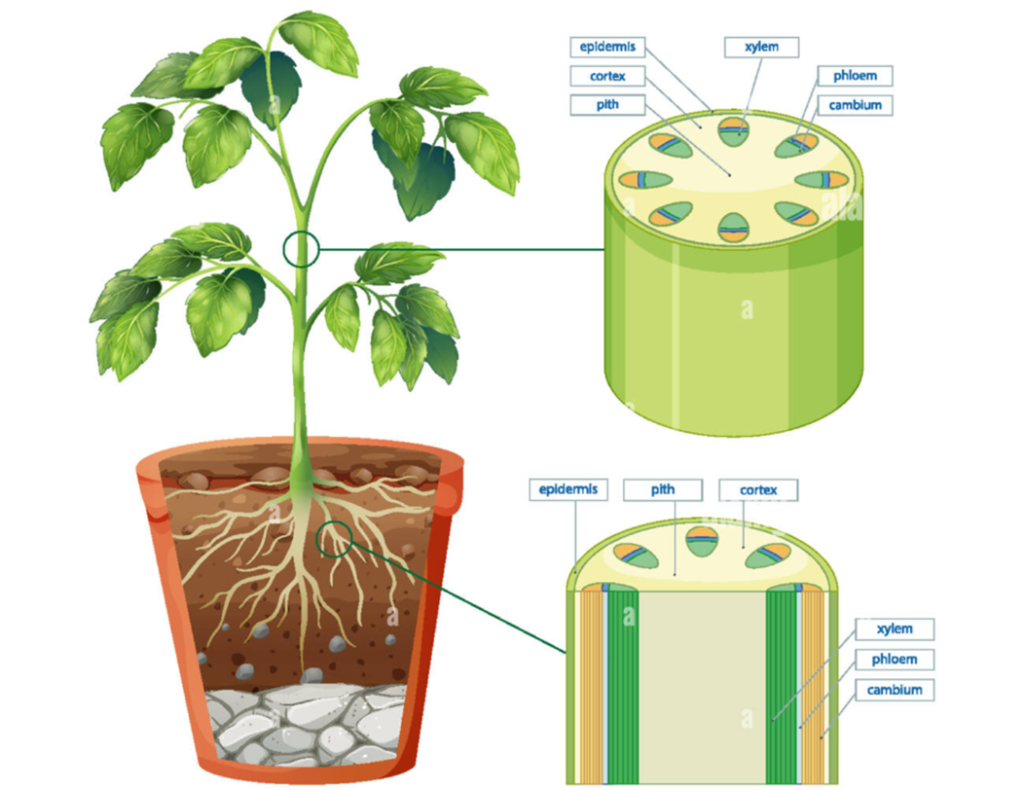

General Anatomy of Root and Stem: Anatomy refers to the internal structure of an organism. In plants, the internal organization of tissues in the root and stem determines their function, growth, and development. The study of their anatomy helps in understanding plant physiology and adaptations to different environments.

General Anatomy of Root and Stem

1. General Anatomy of the Root

Definition & Function: The root is the underground part of the plant responsible for anchorage, water absorption, conduction of minerals, and storage of food. Its internal structure is divided into different layers that perform specialized functions.

Internal Structure of the Root

The transverse section (T.S.) of a typical dicot and monocot root consists of the following layers:

(i) Epidermis (Rhizodermis or Piliferous Layer): The epidermis (rhizodermis or piliferous layer) is the outermost single layer of cells in the root. It has the following characteristics:

- Lacks cuticle and stomata to facilitate water absorption.

- Bears root hairs, which are unicellular extensions that increase surface area for the absorption of water and minerals from the soil.

This specialized structure helps in efficient nutrient uptake, playing a crucial role in plant growth and survival.

(ii) Cortex: The cortex is located beneath the epidermis in the root and has the following features:

- Composed mainly of parenchyma cells, which are loosely arranged and often involved in food storage and facilitating the transport of absorbed substances.

- In monocot roots, the cortex is generally more developed compared to dicot roots. This development supports better storage and transport functions in monocots.

The cortex is essential for the root’s overall function, as it assists in the storage of starch and the movement of water and nutrients from the epidermis to other parts of the root.

(iii) Endodermis: The endodermis is the innermost layer of the cortex and serves as a crucial barrier in the root. Its key characteristics include:

- Composed of barrel-shaped cells that are tightly packed.

- Contains Casparian strips—bands of lignin and suberin that prevent the passive flow of water and solutes through cell walls, forcing them to pass through the plasma membrane.

- Functions as a selective barrier, regulating the movement of water and minerals into the vascular tissues (xylem and phloem).

This selective permeability ensures controlled absorption of nutrients while preventing harmful substances from entering the vascular system.

(iv) Stele (Central Cylinder)

The stele includes the following components:

(a) Pericycle: The pericycle is the outermost layer of the vascular cylinder, consisting of a single layer of thin-walled cells. It functions as a meristematic tissue, giving rise to lateral roots and, in dicot roots, contributing to the formation of vascular cambium for secondary growth.

(b) Vascular Bundles: The vascular bundles in roots consist of xylem and phloem, arranged in a radial manner, meaning they are present on alternate radii.

Xylem: Conducts water and minerals from the roots to the rest of the plant.

Phloem: Transports food (sugars and nutrients) from the leaves to different plant parts.

Root-Specific Arrangement:

Dicot Root: Xylem is arranged in a star shape, with 4-6 patches of xylem (tetrach to hexarch).

Monocot Root: Has more than six patches of xylem (polyarch condition).

This structure ensures efficient transport of essential substances, supporting plant growth and development.

(c) Pith: The pith is the central region of the root, composed of parenchymatous cells that store nutrients and provide structural support.

Dicot Roots: The pith is small or absent, as xylem occupies most of the central region.

Monocot Roots: The pith is well-developed and large, occupying a significant portion of the root’s central area.

The pith plays a role in food storage and contributes to the overall mechanical strength of the root.

Comparison Between Monocot and Dicot Roots

| Feature | Dicot Root | Monocot Root |

| Xylem | 2-6 patches (Tetrarch, Pentarch) | More than 6 patches (Polyarch) |

| Pith | Small or absent | Large and well-developed |

| Cambium | Forms during secondary growth | Absent |

| Secondary Growth | Present | Absent |

2. General Anatomy of the Stem

Definition & Function: The stem is the aerial part of the plant that supports leaves, flowers, and fruits. It is responsible for transporting water, minerals, and food, as well as for mechanical support and storage.

Internal Structure of the Stem

A transverse section (T.S.) of a typical dicot and monocot stem consists of the following layers:

(i) Epidermis: The epidermis is the outermost layer of the stem, serving as a protective barrier. It is covered with a waxy cuticle, which helps reduce water loss and prevent dehydration. The epidermis also contains stomata, facilitating gaseous exchange, and trichomes (hairs) that provide protection against herbivores and excessive water loss. This layer plays a crucial role in shielding the stem from environmental stress while regulating water balance.

(ii) Cortex: The cortex is located beneath the epidermis and plays a vital role in support, storage, and transport. It consists of three main tissues: collenchyma, which provides mechanical support to the stem; parenchyma, which stores food and aids in metabolic functions; and the endodermis, which forms the inner boundary of the cortex and is rich in starch, often referred to as the starch sheath. This structural organization helps in maintaining the strength and functionality of the stem.

(iii) Stele (Vascular Region)

(a) Pericycle: The pericycle is a layer of cells located beneath the endodermis and plays a crucial role in plant growth. It is responsible for giving rise to lateral branches, aiding in root and shoot development. In dicot stems, the pericycle also contributes to secondary growth, helping in the formation of vascular tissues and increasing the thickness of the stem.

(b) Vascular Bundles: The vascular bundles in the stem consist of xylem and phloem, which are responsible for transporting water, minerals, and nutrients throughout the plant.

Dicot Stem: The vascular bundles are arranged in a ring and are open and collateral, meaning they contain a cambium layer, which enables secondary growth (increase in stem thickness).

Monocot Stem: The vascular bundles are scattered throughout the ground tissue and are closed and collateral, meaning they lack cambium, preventing secondary growth.

This structural difference between dicot and monocot stems affects their ability to grow in thickness over time.

(c) Pith: The pith is the central region of the stem, composed of parenchymatous cells that function in food storage and conduction. In dicot stems, the pith is large and well-developed, occupying a significant portion of the central region. In monocot stems, the pith is reduced or absent due to the scattered arrangement of vascular bundles. This structural variation influences the overall storage capacity and conduction efficiency of the stem.

Comparison Between Monocot and Dicot Stems

| Feature | Dicot Stem | Monocot Stem |

| Vascular Bundle Arrangement | In a ring | Scattered throughout |

| Presence of Cambium | Present (Open) | Absent (Closed) |

| Secondary Growth | Present | Absent |

| Pith | Large and well-developed | Reduced |

| Xylem & Phloem | Well-organized | Randomly distributed |

Leaf of Monocotyledons & Dicotyledons

A leaf is a lateral, flattened structure of the plant that develops from the node of the stem or branch. It plays a crucial role in photosynthesis, transpiration, gaseous exchange, and storage. The internal structure of a leaf varies between monocotyledonous (monocot) and dicotyledonous (dicot) plants, reflecting their adaptation to different environmental conditions.

1. External Morphology of a Leaf

A typical leaf consists of the following parts:

(i) Leaf Blade (Lamina): The leaf blade (lamina) is the expanded, flat portion of the leaf, primarily responsible for photosynthesis. It contains veins and veinlets, which provide mechanical support and facilitate the transport of water, minerals, and nutrients throughout the leaf. The broad surface of the lamina maximizes light absorption, aiding in efficient food production for the plant.

(ii) Petiole: The petiole is the stalk that connects the leaf blade to the stem, providing structural support and flexibility. It helps in raising the leaf for better light absorption and air circulation, enhancing photosynthesis and gas exchange. In dicot plants, the petiole is distinct and well-developed, whereas in monocot plants, leaves are often sessile (lacking a petiole) and directly attached to the stem.

(iii) Leaf Base: The leaf base is the part of the leaf that attaches it to the stem. In dicot plants, the leaf base may bear stipules, making the leaves stipulate. In monocot plants, the leaf base often extends to form a sheath that partially or completely surrounds the stem, providing additional support. This structural adaptation helps in anchoring the leaf and facilitating nutrient flow between the stem and the leaf.

2. Venation in Monocot & Dicot Leaves

Venation refers to the arrangement of veins in the leaf lamina.

| Feature | Monocot Leaf | Dicot Leaf |

| Venation Type | Parallel venation (veins run parallel) | Reticulate venation (veins form a network) |

| Example | Grass, Maize, Wheat | Mango, Rose, Peepal |

3. Internal Anatomy of Monocot & Dicot Leaves

A transverse section (T.S.) of a monocot and dicot leaf shows differences in the arrangement of tissues.

(i) Epidermis: The epidermis is the outermost protective layer of the leaf, consisting of a single layer of cells on both the upper and lower surfaces. It is covered with a cuticle, which helps reduce water loss and protect against environmental stress. Stomata are present to facilitate gaseous exchange and transpiration. In monocot leaves, stomata are found on both surfaces (amphistomatic), while in dicot leaves, they are primarily located on the lower epidermis (hypostomatic), minimizing excessive water loss.

(ii) Mesophyll: The mesophyll is the photosynthetic tissue located between the upper and lower epidermis of the leaf. It plays a crucial role in photosynthesis and gas exchange.

In dicot leaves, the mesophyll is differentiated into:

Palisade mesophyll: Columnar cells rich in chloroplasts, primarily responsible for photosynthesis.

Spongy mesophyll: Loosely arranged cells with air spaces, facilitating gaseous exchange and transpiration.

In monocot leaves, the mesophyll is not differentiated into palisade and spongy layers, and the cells are more uniformly distributed throughout the tissue.

(iii) Vascular Bundles (Veins and Veinlets)

The vascular bundles (veins and veinlets) in leaves are responsible for the transport of water, minerals, and food. They consist of xylem, which conducts water, and phloem, which transports nutrients. In dicot leaves, the vascular bundles are large and surrounded by bundle sheath cells, providing structural support. In monocot leaves, there are numerous small vascular bundles, each enclosed by a bundle sheath. In C4 plants, the bundle sheath cells play a crucial role in Kranz anatomy, aiding in efficient carbon fixation and photosynthesis.

Comparison of Monocot & Dicot Leaf Anatomy

| Feature | Monocot Leaf | Dicot Leaf |

| Stomata Distribution | Present on both surfaces | Mostly on lower surface |

| Mesophyll Differentiation | Not differentiated | Differentiated into palisade and spongy |

| Vascular Bundles | Numerous and scattered | Large and fewer |

| Bundle Sheath | Prominent, with Kranz anatomy in C4 plants | Present but less developed |

4. Adaptations in Monocot & Dicot Leaves

Adaptations in Monocot Leaves

- Parallel venation prevents damage and allows efficient nutrient transport.

- Kranz anatomy in C4 plants like maize improves photosynthetic efficiency.

- Tightly packed vascular bundles provide mechanical strength.

Adaptations in Dicot Leaves

- Reticulate venation provides better mechanical support.

- Palisade mesophyll maximizes light absorption.

- Air spaces in spongy mesophyll enhance gaseous exchange.

5. Functions of the Leaf

1. Photosynthesis – Converts light energy into chemical energy (glucose).

2. Transpiration – Removes excess water, cooling the plant.

3. Gaseous Exchange – Takes in CO₂ for photosynthesis and releases O₂.

4. Storage of Food – Some leaves store starch (e.g., Onion).

5. Vegetative Propagation – Some plants reproduce through leaves (e.g., Bryophyllum).

Conclusion

The root and stem of plants are structurally specialized to perform various physiological functions. While the root ensures water absorption and anchorage, the stem supports aerial structures and enables nutrient transport. Understanding their anatomy helps in the study of plant physiology, growth patterns, and adaptation strategies.

Suggested Post: Morphology of Flowering Plants