Lymph circulation is a vital physiological process that ensures the movement of lymph—a clear fluid containing white blood cells, proteins, lipids, and waste products—through the lymphatic system and eventually back into the bloodstream. This circulation plays a crucial role in fluid balance, immune function, and nutrient transport. Unlike the cardiovascular system, which is a closed-loop system driven by the heart, the lymphatic system relies on passive mechanisms such as muscle contractions, breathing, and one-way valves to propel lymph throughout the body.

Anatomy of Lymph Circulation

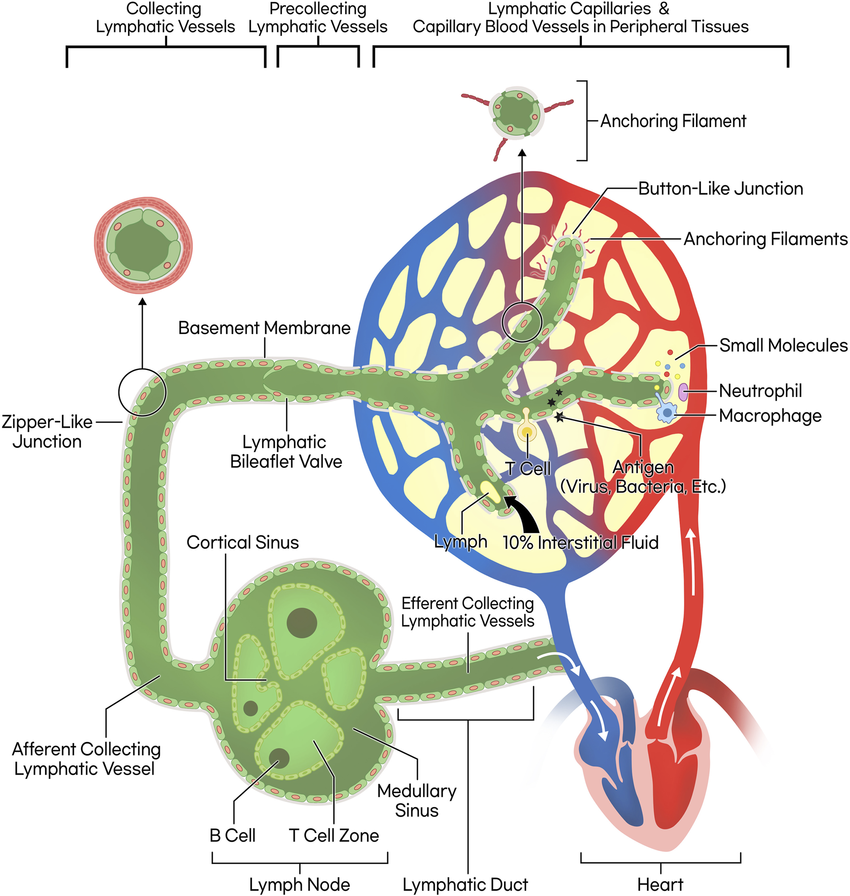

The lymphatic circulation consists of lymphatic capillaries, larger lymphatic vessels, lymph nodes, lymphatic trunks, and lymphatic ducts. The flow of lymph follows a unidirectional pathway:

- Lymph Formation in Tissues: Lymph originates from interstitial fluid, which leaks out from blood capillaries into the surrounding tissues. This fluid enters the lymphatic capillaries, forming lymph.

- Lymphatic Capillaries: These blind-ended, highly permeable vessels absorb interstitial fluid, proteins, and immune cells. The overlapping endothelial cells act as one-way valves, allowing fluid entry but preventing leakage.

- Larger Lymphatic Vessels: Lymph capillaries merge into larger lymphatic vessels that contain valves to prevent backflow. These vessels transport lymph toward lymph nodes, where immune filtration occurs.

- Lymph Nodes (Filtration Centers): Lymph flows through lymph nodes, where immune cells (macrophages, lymphocytes) filter pathogens, cellular debris, and abnormal cells. The purified lymph then moves toward larger vessels.

- Lymphatic Trunks: Multiple lymphatic vessels combine to form lymphatic trunks, which drain lymph from specific regions of the body.

The major lymphatic trunks include:

- Jugular Trunks (drain the head and neck)

- Subclavian Trunks (drain the upper limbs)

- Bronchomediastinal Trunks (drain the thoracic cavity)

- Lumbar Trunks (drain the lower limbs and pelvis)

- Intestinal Trunk (drains the digestive organs)

- Lymphatic Ducts (Final Collection Pathway): Lymphatic trunks merge into two major lymphatic ducts, which empty lymph into the venous system:

- Right Lymphatic Duct → Drains lymph from the right upper limb, right side of the head, and right thorax into the right subclavian vein.

- Thoracic Duct (Largest Lymphatic Vessel) → Drains lymph from the rest of the body into the left subclavian vein.

- Return to Bloodstream: The collected lymph re-enters the circulatory system, ensuring fluid homeostasis and preventing edema.

Mechanisms of Lymph Circulation

Since the lymphatic system lacks a central pump (like the heart in the circulatory system), lymph movement relies on several passive mechanisms:

1. Skeletal Muscle Contraction: Skeletal muscle movements compress lymphatic vessels, pushing lymph forward.This mechanism is essential in the lower limbs, where gravity can slow lymph movement.

2. Respiratory Pump (Breathing Movements): During inhalation, the diaphragm creates pressure changes that help move lymph upward.

3. Valves in Lymphatic Vessels: One-way valves prevent backflow, ensuring lymph moves only toward the subclavian veins.

4. Smooth Muscle Contraction: Larger lymphatic vessels contain smooth muscle, which contracts rhythmically to propel lymph.

5. Arterial Pulsations: Lymphatic vessels located near arteries benefit from arterial pulsations, which create pressure waves that assist in lymph flow.

6. Body Movements and Gravity: Postural changes, walking, and stretching influence lymph movement.

Functions of Lymph Circulation

Lymph circulation plays a vital role in maintaining homeostasis and immune defense. Its key functions include:

1. Fluid Balance and Prevention of Edema: Prevents tissue swelling (edema) by absorbing excess interstitial fluid.Returns fluid to the circulatory system, maintaining blood volume and pressure.

2. Immune Surveillance and Defense: Lymph carries pathogens, toxins, and antigens to lymph nodes for immune filtration.Lymphocytes and macrophages destroy harmful invaders before lymph re-enters circulation.

3. Fat Absorption and Transport: Specialized lymphatic capillaries (lacteals) in the intestine absorb dietary lipids and fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K).These fats are transported as chyle to the bloodstream.

4. Waste Removal: Removes cellular debris, metabolic waste, and foreign particles from tissues.

Disorders Related to Lymph Circulation

Dysfunction in lymph circulation can result in various medical conditions:

1. Lymphedema: Blockage or damage to lymphatic vessels leads to fluid accumulation in tissues, causing swelling, pain, and stiffness.

Causes include:

Primary lymphedema (genetic defects in lymphatic development).

Secondary lymphedema (due to surgery, radiation, trauma, or infections like filariasis).

2. Lymphangitis: Inflammation of lymphatic vessels due to bacterial infections.Symptoms include red streaks on the skin, fever, and swollen lymph nodes.

3. Chylothorax: Leakage of chyle (fat-rich lymph) into the chest cavity due to trauma or cancer.Leads to respiratory distress and requires medical intervention.

4. Lymphatic Filariasis (Elephantiasis): A parasitic infection (caused by Wuchereria bancrofti) leads to severe lymphedema and thickening of the skin.Transmitted through mosquito bites.

5. Cancer Metastasis via Lymphatics: Cancer cells can enter lymphatic vessels and spread to distant organs.Lymph node biopsy helps assess cancer progression.

Conclusion

Lymph circulation is a fundamental physiological process that maintains fluid balance, immune defense, and nutrient transport. Unlike the cardiovascular system, lymphatic circulation relies on skeletal muscle contractions, respiratory movements, and valves for fluid movement. Disorders affecting this circulation can lead to lymphedema, infections, and cancer metastasis, making it a crucial area in medical research and clinical practice.

Join Our Telegram Channel

Join Our Telegram Channel