The pulse is the rhythmic expansion and recoil of an artery caused by the ejection of blood from the heart, specifically the left ventricle, during systole. It is one of the vital signs used to assess a person’s cardiovascular health and provides critical information about heart rate, rhythm, and the condition of the circulatory system. Each pulse beat corresponds to one cardiac cycle, making it an essential, non-invasive clinical tool to evaluate cardiac function.

See also: Anatomy of the heart

Definition of Pulse

Pulse is defined as the transient increase in arterial pressure that can be felt during palpation due to the contraction of the left ventricle. It reflects the pressure wave that travels through the arterial system and is typically measured by placing fingers over a superficial artery.

Physiology of Pulse

Pulse Formation: The formation of the pulse begins when the left ventricle contracts and ejects blood into the aorta during systole. This action generates a pressure wave that travels along the arteries, causing them to expand and recoil. This pulse wave moves faster than the actual flow of blood and can be felt at various pulse points throughout the body a fraction of a second after the heart’s contraction.

Characteristics of Pulse

Rate: The pulse rate indicates the number of beats per minute (bpm). A normal resting pulse rate in adults is typically between 60 to 100 bpm. When the rate drops below 60 bpm, it is referred to as bradycardia, which may be normal in athletes or a sign of underlying pathology. A rate above 100 bpm is called tachycardia and can be caused by fever, exercise, anxiety, or disease.

Rhythm: The rhythm of the pulse describes the regularity of the beats. A normal rhythm is regular and consistent. An irregular rhythm can indicate cardiac arrhythmias, such as atrial fibrillation or premature beats, which require further evaluation.

Volume (Amplitude): Volume or amplitude refers to the strength or fullness of the pulse. A strong and bounding pulse usually reflects good stroke volume, whereas a weak or thready pulse may be a sign of low cardiac output, hypovolemia, or heart failure.

Tension: Tension is related to the resistance of the arterial wall to the pressure wave. A high-tension pulse is commonly observed in hypertensive individuals, whereas a low-tension pulse may be seen in conditions with reduced peripheral resistance.

Equality: Both sides of the body should have equal pulse volume and rhythm. Any discrepancy may suggest a vascular obstruction, aneurysm, or stenosis on the affected side.

Condition of the Arterial Wall: The arterial wall should feel smooth and elastic under palpation. If it feels hard or calcified, this may suggest atherosclerosis or age-related vascular changes.

Types of Pulse

Pulse patterns may vary due to pathological or physiological conditions. A tachycardic pulse, with a rate greater than 100 bpm, may occur due to fever, hyperthyroidism, or anemia. Bradycardia, or a slow pulse below 60 bpm, may be found in athletes or individuals with heart block or hypothyroidism. A thready pulse is weak and difficult to detect, often seen in shock or heart failure. A bounding pulse is strong and forceful and may occur during fever, anxiety, or in conditions like aortic regurgitation. An irregular pulse is uneven and may indicate arrhythmias. A bigeminal pulse is characterized by two beats followed by a pause, often caused by premature ventricular contractions. Pulsus paradoxus is a pulse that becomes weaker during inspiration and is typically seen in cardiac tamponade or asthma. Pulsus alternans refers to alternating strong and weak beats, which suggest left ventricular failure. A water-hammer pulse is a bounding and collapsing pulse that is commonly associated with aortic regurgitation.

There are several clinical terms for different kinds of abnormal pulse patterns:

| Type of Pulse | Description | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Tachycardia | Fast pulse >100 bpm | Fever, anemia, hyperthyroidism |

| Bradycardia | Slow pulse <60 bpm | Athletes, heart block, hypothyroidism |

| Thready (Weak) Pulse | Low volume and hard to feel | Shock, heart failure |

| Bounding Pulse | Very strong pulse | Fever, anxiety, aortic regurgitation |

| Irregular Pulse | Uneven rhythm | Arrhythmias (e.g., AFib) |

| Bigeminal Pulse | Two beats followed by a pause | Premature ventricular contractions |

| Pulsus Paradoxus | Pulse weakens during inspiration | Cardiac tamponade, asthma |

| Pulsus Alternans | Alternating strong and weak beats | Left ventricular failure |

| Water-Hammer Pulse | Rapid and forceful with quick collapse | Aortic regurgitation |

Sites for Palpating the Pulse

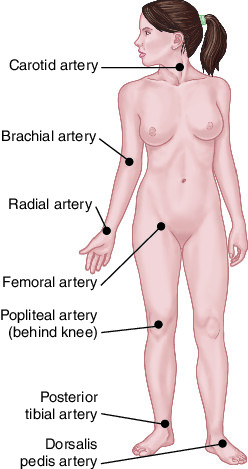

The pulse can be palpated over superficial arteries that lie close to the surface of the body and over firm structures. The radial pulse is felt on the wrist, lateral to the radius bone. The carotid pulse is located in the neck between the trachea and sternocleidomastoid muscle. The brachial pulse is felt in the antecubital fossa of the elbow. The femoral pulse is palpated in the groin. The popliteal pulse is located behind the knee. The dorsalis pedis pulse is found on the top of the foot, while the posterior tibial pulse is located behind the medial malleolus of the ankle. The temporal pulse is felt on the lateral aspect of the forehead.

The pulse can be palpated at various superficial arteries located over firm structures like bone. Common pulse points include:

| Site | Artery Involved | Location |

|---|---|---|

| Radial pulse | Radial artery | Wrist (lateral to radius) |

| Carotid pulse | Common carotid artery | Neck (between sternocleidomastoid and trachea) |

| Brachial pulse | Brachial artery | Antecubital fossa (elbow) |

| Femoral pulse | Femoral artery | Groin area |

| Popliteal pulse | Popliteal artery | Behind the knee |

| Dorsalis pedis pulse | Dorsalis pedis artery | Top of the foot |

| Posterior tibial pulse | Posterior tibial artery | Behind the medial malleolus of ankle |

| Temporal pulse | Superficial temporal artery | Lateral aspect of the forehead |

Factors Affecting Pulse

Pulse rate and quality can be influenced by various internal and external factors.

Age: Age plays a significant role; newborns typically have a pulse rate of 120–160 bpm, children range from 80–100 bpm, adults from 60–100 bpm, and elderly individuals may have slightly lower pulse rates due to a reduced metabolic rate.

Gender: Gender can influence the pulse, as females usually have slightly higher rates than males.

Physical activity: Physical activity temporarily increases the pulse, while trained athletes may have a lower resting pulse due to improved cardiac efficiency.

Body temperature: Body temperature affects pulse as well; for every 1°C rise in body temperature, the pulse rate can increase by about 10 bpm.

Emotions and stress: Emotions and stress activate the sympathetic nervous system, leading to an increased pulse.

Medications: Medications such as beta-blockers reduce the pulse rate by inhibiting sympathetic activity, while agents like epinephrine increase it by stimulating adrenergic receptors.

Disease conditions: Disease conditions such as shock, hypoxia, or hemorrhage can significantly alter the pulse in both rate and quality.

Pulse and Cardiac Output

Pulse is closely related to cardiac output, which is defined as the product of heart rate and stroke volume. Any factor affecting heart rate or the volume of blood ejected with each beat will have a direct impact on cardiac output. A strong, regular pulse generally indicates efficient cardiac output, while a weak or irregular pulse may suggest compromised heart function.

Pulse vs Heart Rate

Although pulse and heart rate are often used interchangeably, they are not always equivalent. Pulse is the tactile arterial palpation of each heartbeat, while heart rate is the number of actual contractions of the heart per minute. In certain arrhythmias such as ventricular fibrillation or pulseless electrical activity, a patient may have electrical activity without a palpable pulse, highlighting the difference between the two.

Pulse Examination Technique

Steps for Radial Pulse Examination:

1. Patient should be in a comfortable position, seated or lying down.

2. Use the pads of your index and middle fingers.

3. Gently press the radial artery against the radius bone.

4. Count for 30 seconds and multiply by 2 (if regular).

5. If irregular, count for a full minute and compare with apical pulse.

Clinical Importance of Pulse

- Vital Sign Monitoring: Pulse is one of the key indicators in triage and routine exams.

- Detecting Arrhythmias: Irregular pulse may be first clue to conditions like atrial fibrillation.

- Shock and Hypovolemia: A weak, thready, rapid pulse suggests poor perfusion.

- Cardiac Arrest: Absence of pulse is a key sign; immediate CPR is required.

- Peripheral Artery Disease: Absent or diminished pulses in legs/feet indicate arterial obstruction.

Conclusion

The pulse is a simple yet powerful indicator of the cardiovascular system’s health. It reflects the heart’s pumping efficiency, vascular integrity, and hemodynamic status. A comprehensive assessment of the pulse—including its rate, rhythm, volume, and quality—can provide critical information for diagnosing and managing a wide range of medical conditions. Understanding how to properly evaluate and interpret pulse findings is an essential skill for all healthcare professionals and plays a key role in ensuring timely and effective patient care.